People’s Park Complex: Heart Transplant in the City Centre 60 Years Ago

The Golden Mile Complex has been vacated recently, entering a new phase of its history as Singapore’s first post-independent private mixed use megastructure to conferred conservation status. As the key landmark in Singapore’s ‘Precinct North 1’ urban renewal pilot project undergoes restoration and adaptive reuse, it is timely to cast the spotlight on People’s Park Complex, a contemporaneous and equally significant urban renewal landmark that bookended the ‘Precinct South 1’ in historic Chinatown, now threatened by enbloc sales and demolition.

“Singapore is an island, only about 210 sq miles in area. The built-up area is only 40 sq miles and within this 20% of land area, there live about 80% of the population”

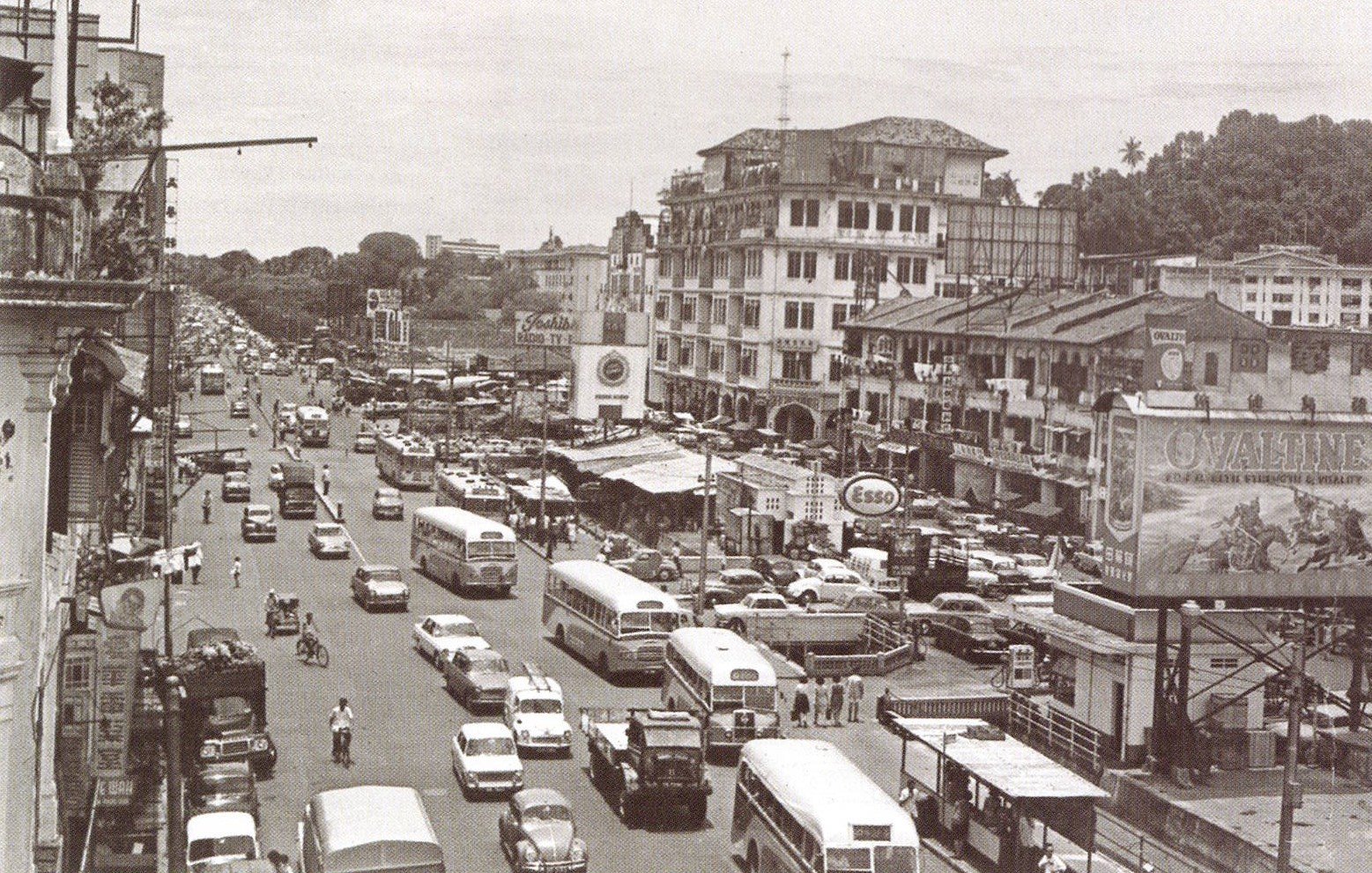

60 years ago, the city centre of Singapore was congested with overcrowded squatters housing the majority of the population. Urban renewal was an urgent priority for the new government to modernise Singapore, and at the crux of the issue were the acute housing shortage and resistance of residents and businesses to resettle from the downtown area. Decrepit shophouses occupied valuable land with significant potential for commercial development, translating to untapped job creation opportunities and lack of economic stimulation.

To create room and move forward with urban redevelopment, immense resolve was undertaken by the government to establish the necessary legislation and action plan. In the early 1960s, the Housing Development Board (HDB) extensively built new public housing estates to resettle the displaced population from the central area. Along with the Land Acquisition Act, land was progressively secured in the downtown area for developmental projects.

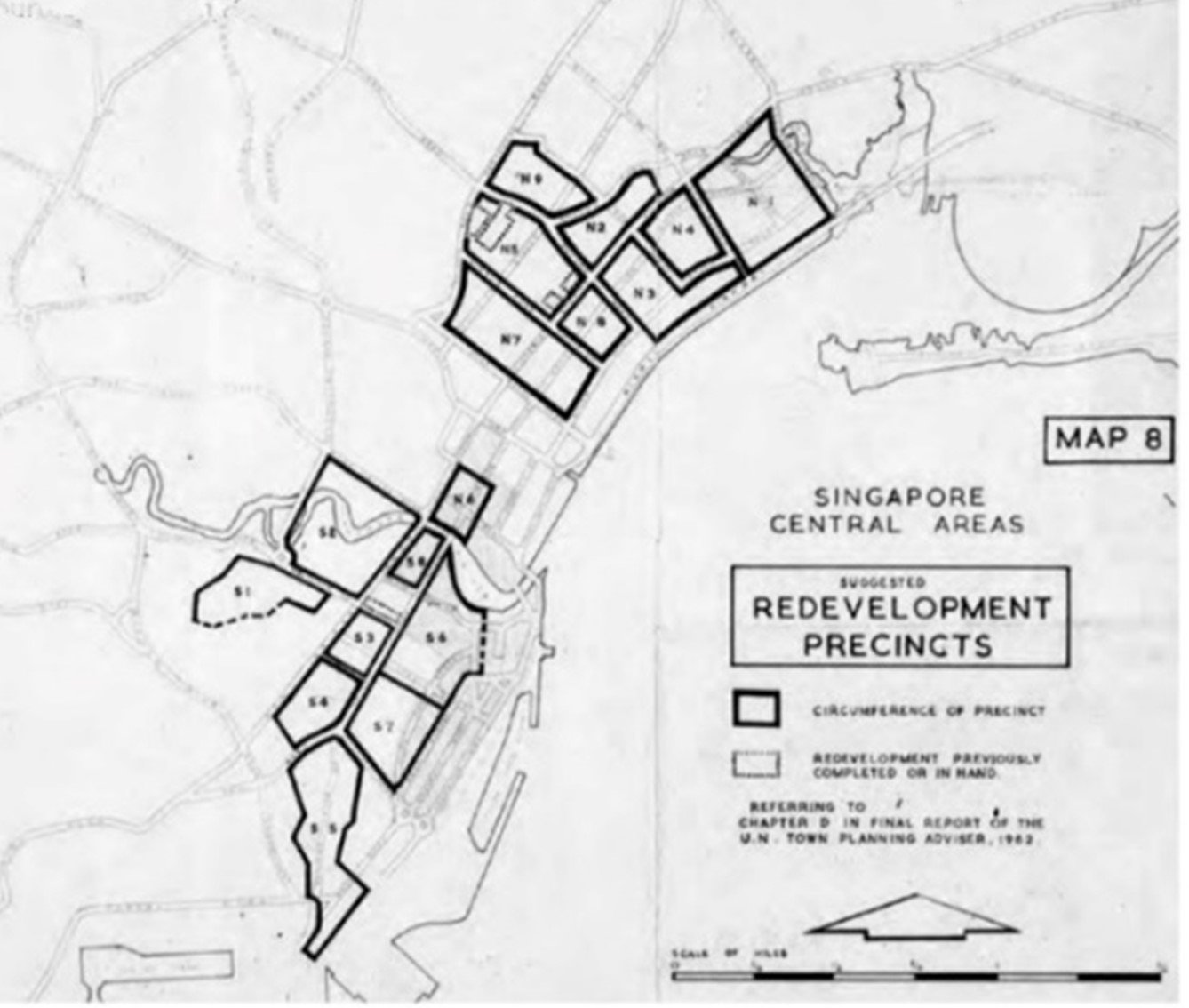

Urban renewal eventually kickstarted in 1966 with the pilot Precinct North 1 (N1) and Precinct South 1 (S1) bookending the north and south of the historic Central Area, respectively. The precinct-scale redevelopment framework was initiated by the town planning expert Erik Lorange, who represented the United Nations in providing technical assistance for the state’s city planning. The idea was to simultaneously redevelop the two pilot precincts at the fringes of the downtown area to “give a two-prong centrifugal action” and then move towards the core around the river where the population was the densest.

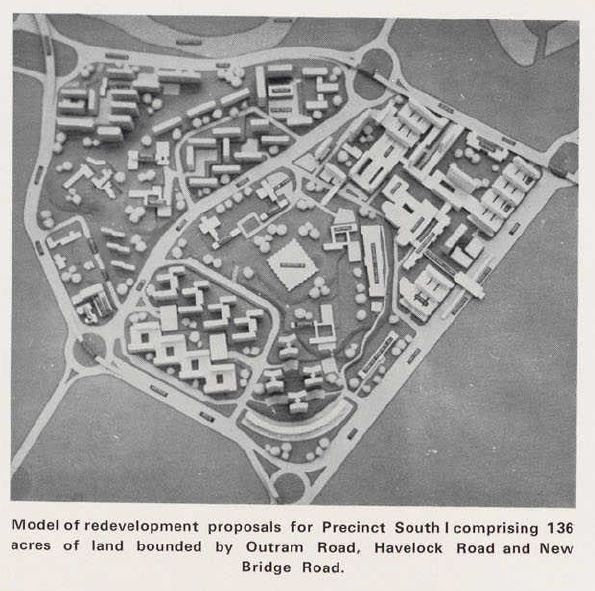

Precinct S1 (bounded by Havelock Road, Outram Road and New Bridge Road; 136 acres) was adjacent to the overcrowded shophouse squatters of Kreta Ayer (present-day Chinatown) and chosen for its potential parcels that could be easily made available – the old People’s Park Market and Outram Prison. Precinct N1, on the other hand, strategically contained a strip of available prime land earmarked for a series of large-scale private development forming the “Golden Mile”. However, the government recognised that public action was insufficient to generate employment and economic growth for the state. In response, the newly formed sub-group Urban Renewal Department (URD) in the HDB launched the first Sale of Sites in 1967 to engage private participation in the redevelopment of tactical portions of the downtown area.

The People’s Park Complex project at Precinct S1, Parcel’ N’ (approx. 111,500 sq ft), was among the earliest collaborations with private developers to complement public projects in delivering the essential impetus for rejuvenating the old Chinese downtown district. The site, where the former People’s Park Market stood, was successfully acquired and sold for redevelopment into ‘Flats and Shopping Complex and Other Commercial Use’. The move was prompted by a coincidental fire in 1966 which partially destroyed the marketplace and reopened the space for re-imagining a modern People’s Park as “a new nucleus within the whole fabric of the city core”.

An Intricate Surgery

“People’s Park (Market) has been a traditional shopping centre for a long time. It is a great centre for bargain goods, particularly for the poorer sections of the community, goods that are generally cheaper than elsewhere so that people from the suburbs also come down to shop, not just to shop but to feel the way of life as it were.”

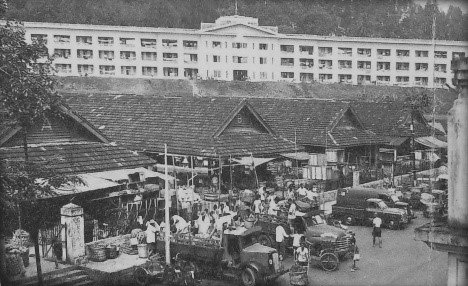

Redeveloping the People’s Park was a delicate task of performing a heart transplant on the city centre. The old People’s Park Market 珍珠巴刹was the historic mercantile nucleus of Kreta Ayer, an essential component generating economic vitality and social life within one of the most populated and traditional Chinese downtown enclaves.

The name “People’s Park” dates back to 1886 when 10 acres of land at the foot of Pearl’s Hill 珍珠山was presented by the British governor to the public in exchange for part of the Hong Lim Green for building a new Police Court. As the name “People’s Park” suggests, the site was intended as a commons park for the people residing in the growing Chinese settlement. By the turn of the century, People’s Park was a recreational ground for the working class that accommodated play facilities, band performances and an expanding hawker community. Both licensed and illegal vendors and petty traders were conglomerating at the park. To abolish street hawking in the 1920s, the Municipal Commissioners installed “special shelters in People’s Park, which are properly roofed and floored, and provided with a water supply” to relocate licensed hawkers from the streets. The humble shelters officially marked the beginnings of the People’s Park Market, and they continued to grow at the foothills up till the 1950s.

Before independence, residential communities and businesses in the city centre formed an intricate, interdependent ecosystem. The archetypal shophouse architecture grew around a mode of economic organisation, where the same premise typically combined both work and domestic activities, and business was very much a family affair.

Operating on a similar basis, the People’s Park Market depended on its centrality and proximity to densely occupied residential areas for economic survival. Many nearby residents were employed by businesses or made a living by operating shops at the People’s Park Market or informal roadside stalls that capitalise on its popularity and customer base. The marketplace was deeply interwoven into the city centre’s urban fabric and socio-economic structure. For over 40 years, it was a popular one-stop destination in Singapore, offering a variety of affordable goods that catered especially to the lower class. With the establishment of the Tien Yien Moi Toi 天演舞台 (later renamed Majestic Theatre大华戏院) and Nam Tin Hotel 南天大酒楼 (Great Southern Hotel) beside the market in 1927, an iconic urban ensemble in the Chinese downtown was convened – an intense confluence of burgeoning commerce, livelihoods, cultural exchanges, and social participation. Until the 1960s, street performances and storytelling were familiar sights. The hustle and bustle from entertainment, everyday conversations and haggling over prices had come to characterise the vibrant atmosphere of the site.

1968 Report on the analysis of The People's Park customer survey. Source: Ministry of Law and National Development

The government was well aware of the intricacy of redeveloping the People’s Park and, by and large, the city centre. As recounted by one of Singapore’s pioneering urban planners, Chua Peng Chye, a two-day survey was conducted at the People’s Park Market under the UN Development Programme Assistance to understand the operations, customer base and appeal of the site to facilitate studies on the impact of the relocation. Underlying the process was the challenge of re-configuring a highly interwoven socio-urban fabric into a new format of high-rise, high-density modern typology. Given the impact on a large population, the resettlement approach had to safeguard the existing business community and minimise the effects on viability and operation efficiency.

United Nations documentary on urban renewal in Singapore in the 1960s. Pioneer urban planner Chua Peng Chye discusses about challenges faced and solutions adopted for redevelopment of the People’s Park.

‘Singapore, My Singapore’ Documentary, 1960s. Source: United Nations Television, via VintageFilmChannel, YouTube.

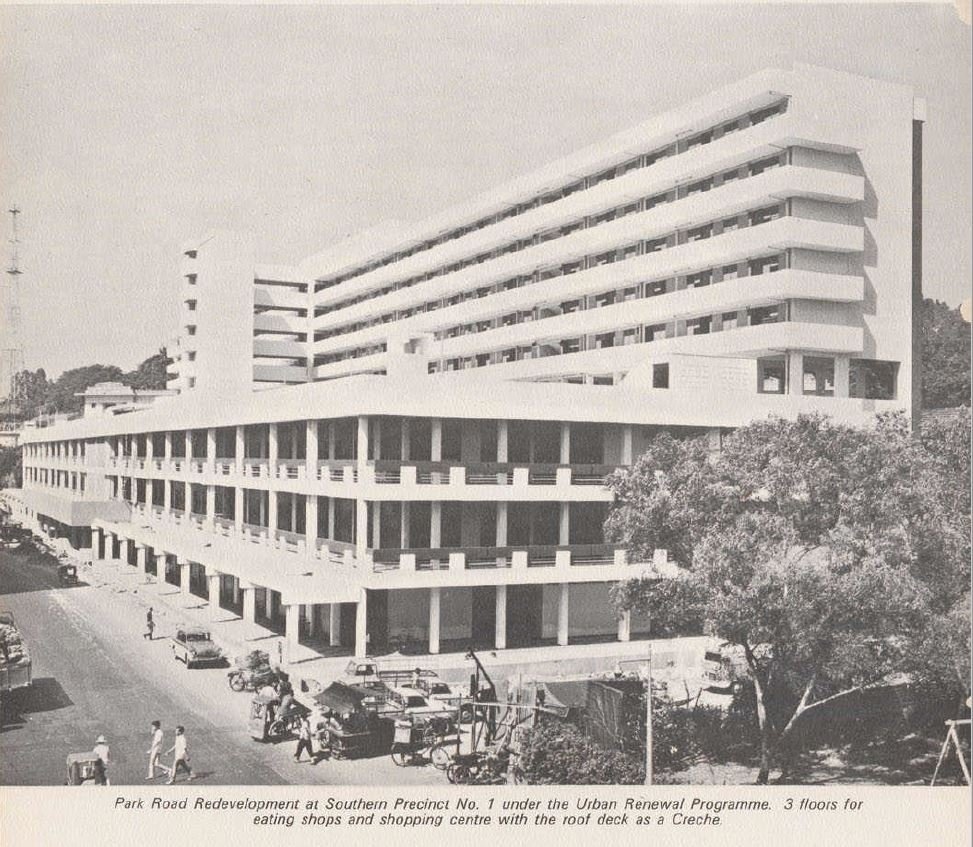

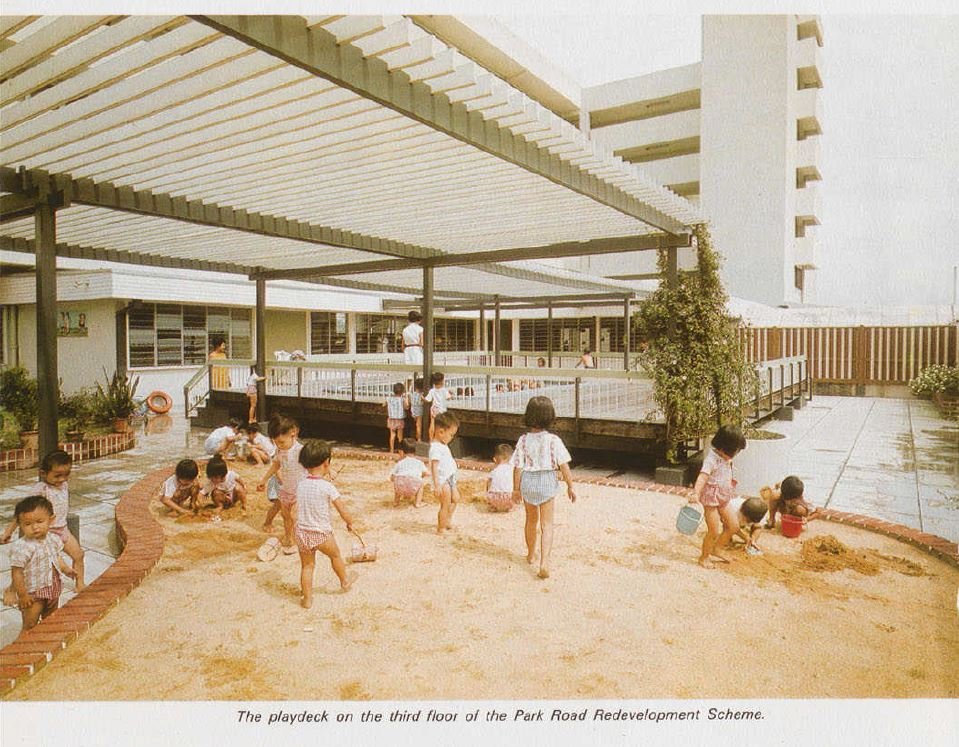

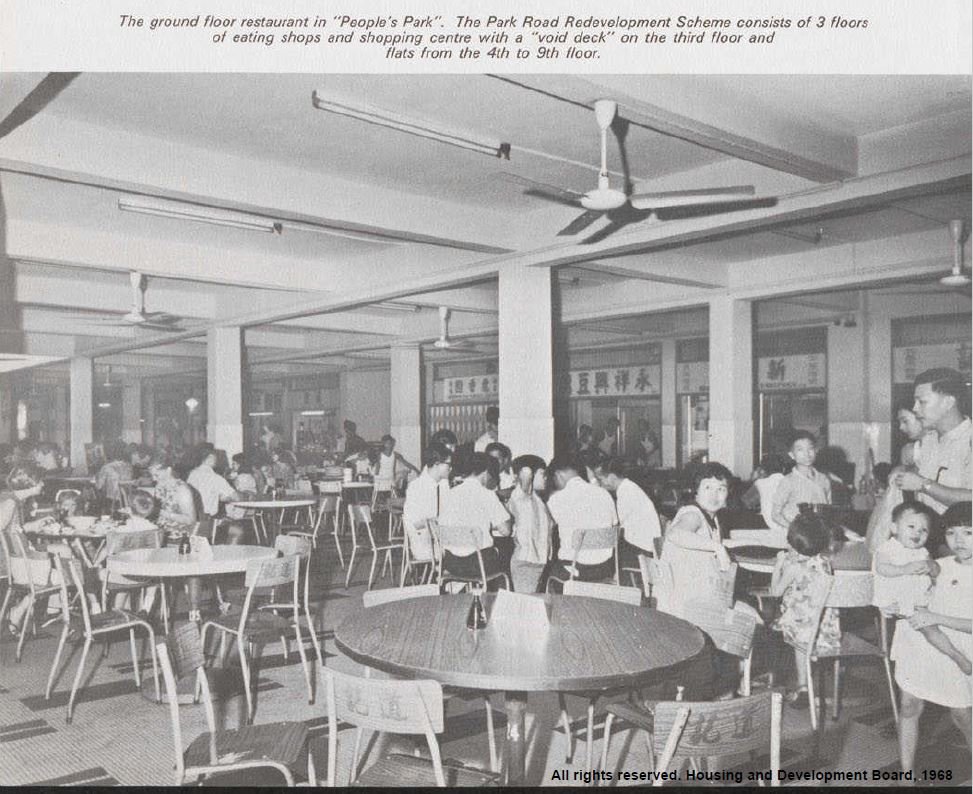

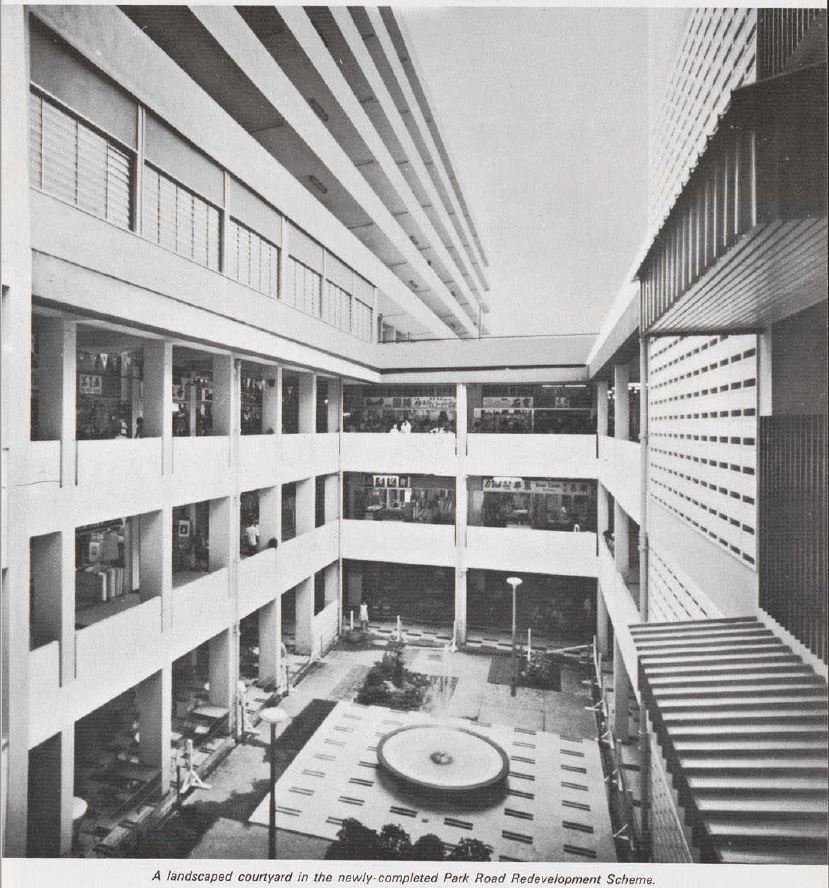

The operation began with the construction of a resettlement centre beside the old People’s Park Market by the HDB, a project known as the Park Road Redevelopment Scheme or the People’s Park Food Centre (32 New Market Road), to relocate stall owners. This was an epochal insertion of the first high-rise, high-density block into the People’s Park urban ensemble. An experimental mixed-use typology – a novelty then – was adopted to allow affected communities to adapt more easily to new high-rise environments. Residential towers were integrated with retail podiums to maintain work-and-home proximity and designed to provide shop frontage with footfall comparable with traditional shophouses.

The Park Road Redevelopment Scheme (People’s Park Food Centre) by the HDB. Source: Housing Development Board Annual Report (1965-68)

Injecting New Blood: Economic Vitality and Modern Culture

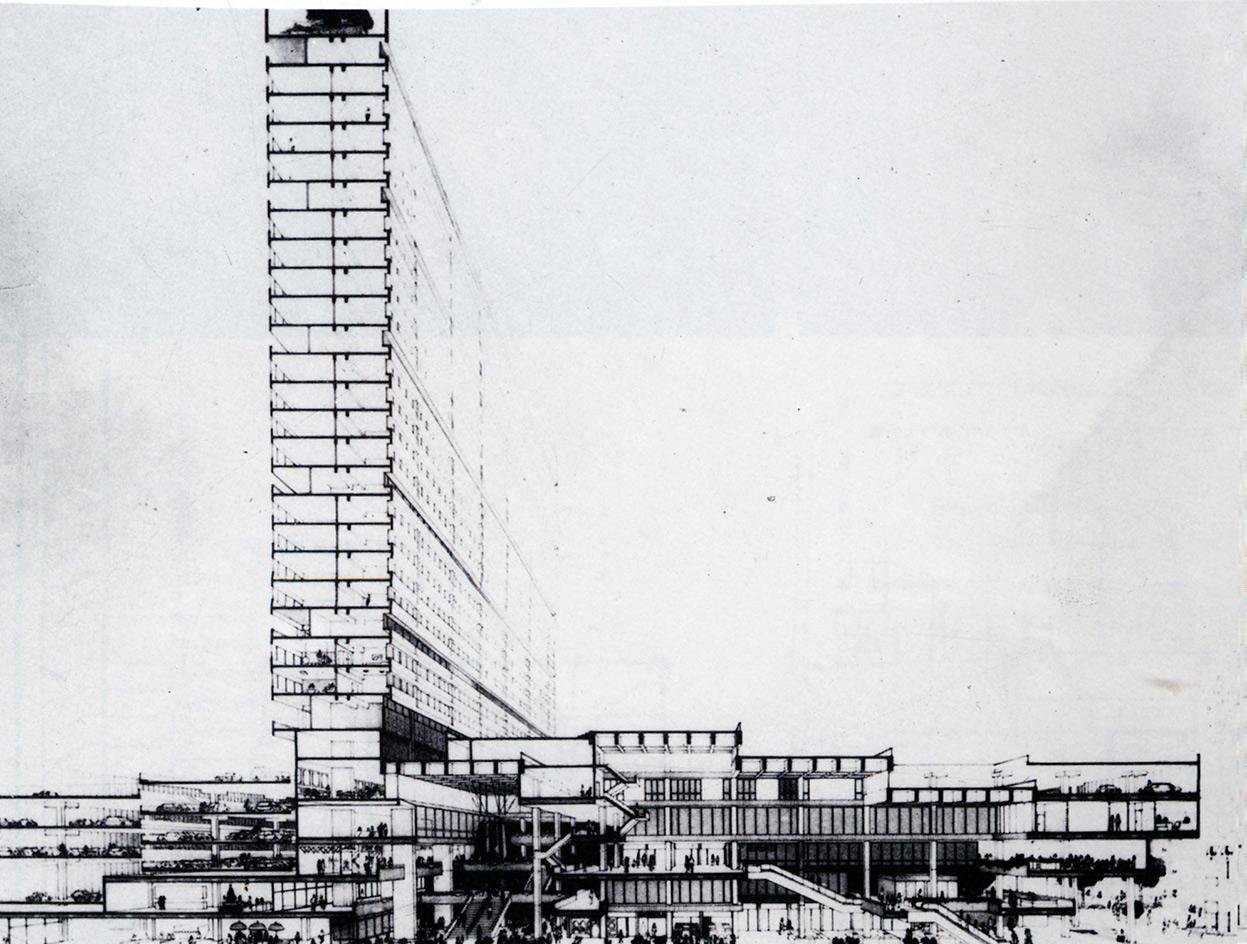

Simulated sketch plan of People’s Park Complex designed by the Urban Renewal Department of the Housing Development Board. Source: SIAJ Journal of the Singapore Institute of Architects.

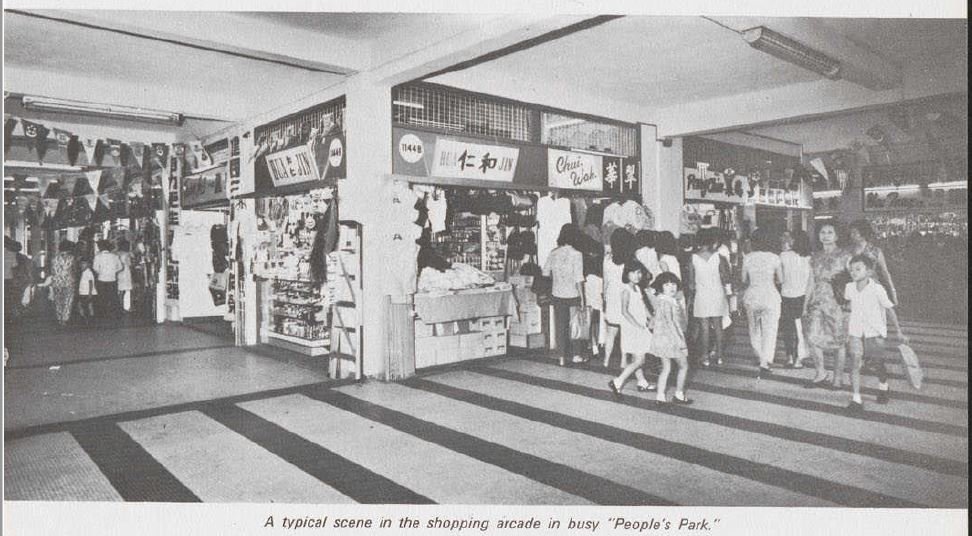

The resettlement of communities from the old People’s Park Market to the adjacent high-rise block created a void in the city centre for re-inventing a modern People’s Park under the rubrics of nation-building and modernisation. Applying the same approach of strata zoning, which produced multi-use buildings, the new complex was stipulated for large-scale retail and residential functions. Unlike its humble counterpart, People’s Park Food Centre, the People’s Park Complex project held a dual ambition: It sought to return the lost vibrancy of the former marketplace and stitch the friable socio-urban fabric while paving ways for a modern culture of retail as the forerunning shopping centre of Singapore.

Under the first Sales of Sites in May 1967, a public tender was announced for the private development of the People’s Park following the designated urban renewal programme combining ‘Flats, shopping complex and other commercial use”. The vision of the urban planners was encapsulated in the ‘simulated sketch plan’ issued with the tender package. Designed by the Urban Renewal Department of the HDB, the sketch plan set the bar for design quality. Developers were given the option to adopt provided scheme or propose an alternative design for the development, and submissions were evaluated for their overall economic return and design merits.

“Selection of tenders will not be based on premium offered alone but will also be judge on the overall economic return and design merits offered”

The developer Ho Kok Cheong and the architecture firm Design Partnership ultimately won the design bid for the milestone project in their first major collaboration. The local practice was founded in the same year (1967) by the young architects William S.W. Lim, Koh Seow Chuan and Tay Kheng Soon. Apart from fulfilling the programmatic requirements set in the brief, the winning counterproposal design embodied the ideologies of the newly independent nation to create a future modern Asian city. The concept was to create a modernist megastructure which reconfigures and accommodates the compactness and intensity of the traditional city centre and the fine-grained urban pattern in which homes and businesses were closely interwoven. Translating characteristics of the former urban fabric dominated by multi-use shophouses into a new high-rise high-density format, the proposed mixed-use development integrates a 5-storey modern air-conditioned shopping podium with a 26-storey residential slab block. The strata-zoning approach enabled a heterogeneous mix of 334 shops, offices, kiosks, and restaurants in various sizes and 260 flat units in 6 different types.

In keeping with the image of the former People’s Park, the architects reinvented energetic public spaces of the historical streets and marketplace by creating two cavernous, interlocking atria within the megastructure. The idea of a large multi-storey indoor void was unprecedented, and the employment of the first shopping atrium in Asia in the People’s Park Complex turned it into a pioneering prototype that influenced generations of shopping malls. The insertion of a ‘city room’ was a recognition that the old People’s Park Market was a key gathering space and the intersection between commerce and social interaction. Against the backdrop of nation-building, the design pursued the civic purpose of returning a collective space to the public domain within the comforts of the building, one that facilitates social participation and inclusivity.

“Singapore needs some of these buildings in the city for all Singaporeans to get together. So we planned this People’s Park with a big, huge concourse, a big, huge atrium…and we were very, very clelar that cities that have buildings like that have a civic space, it’s a people’s space, and we call it a ‘city room”

Completed in 1973, the People’s Park Complex met with great success and popularity. The building was repeatedly celebrated as an exemplary urban model for modern and humanised commercialism. The paradigm shift in programmatic zoning produced a social collision between disparate programmatic functions, whereas the civic component, the ‘city room’, re-injected vitality that was dissipating from the downtown district.

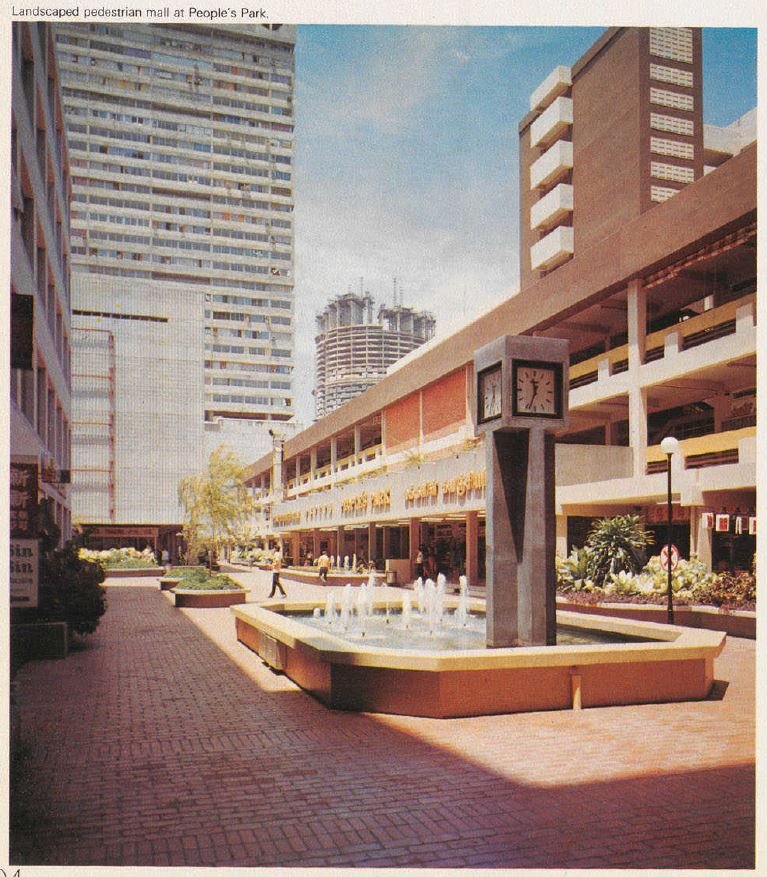

The major urban operation was concluded with the creation of a pedestrianised and landscaped public square by the URD to provide relief and complement the intensive developmental projects in People’s Park. Bounded by the People’s Park Complex, People’s Food Centre, Ocean Group (OG) Departmental Store (completed in 1972) and Majestic Theatre, the T-shape plaza taps into a much larger urban pedestrian network. It is positioned at the confluence of several paths between the neighbouring buildings. Adorned by kiosks, seating, planters, fountains and a clock tower, the public square functioned as an urban node for everyday interaction and community gathering.

An intricate heart transplant in the city centre, the 1960s redevelopment of People’s Park represents an important milestone in the urban developmental history of Singapore. From city planning and resettlement of communities to land sales tender and design conception, every step was complex and demanded paramount sensitivity to safeguard the socio-urban fabric and zeitgeist of the former People’s Park Market. The People’s Park Complex and People’s Park Food Centre are significant testimonies that urban redevelopment and tradition need not be at odds. Developed by private developers, architects and public hands with civic responsibility, the People’s Park buildings collectively conceptualised modern retail culture by reinterpreting the site’s historical marketplace and larger heterogeneous urban condition, fulfilling the urban renewal visions of the post-independence nation.

Disclaimer:

This essay was prepared by Eng Jia Wei in her personal capacity. The opinion expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of Docomomo Singapore.